As with most things at the time, the writing world was predominantly men—if a woman was published, it was usually done via pseudonym. Nobody wanted to read a woman’s thoughts. However, the turn of the century stirred up society, industry, and the arts. We started seeing female names in print, even if they weren’t “feminist” in the way we think of it today. Here are our picks for the most influential female authors of the 19th century who published incredible stories during the 1800s.

10. Elizabeth Gaskell (1810–1865)

Interestingly, Elizabeth Gaskell wrote the very first biography of Charlotte Brontë (1857), who also appears later on this list. Talk about a small world! A lot of Gaskell’s nonfiction work was used by historians to study the Victorian era, especially her detailed descriptions of the poverty class, who weren’t usually focused on (except by Charles Dickens). But all of that isn’t why Gaskell is on our list. We picked the English novelist for her 1854 social novel North and South, which Charles Dickens himself picked out when he published it for her! The British media have been all over it since, with three adaptations and a spin-off so far. Just don’t get it confused with the ABC miniseries (1985–1994) of the same title and time setting!

9. Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861)

You probably haven’t heard of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, but you’ve definitely heard of Edgar Allan Poe or Emily Dickinson! Browning was the poet who inspired those big names, having written sonnets that would have Shakespeare shaking in his boots. Epic poetry, novels, and love ballads make up her two-volume-thick 1844 collection called Poems, written despite her chronic health problems. Browning started writing poetry at just 11 years old, which her mother hoarded (luckily for us) into the biggest collection of juvenilia in English history. On top of her swooning sonnets and secret marriage, Browning was also an advocate against slavery and child labor.

8. Kate Chopin (1850–1904)

In retrospect, if critics of the 1890s labeled something as “immoral,” that was a pretty good sign that it was a great book. Catholics of the American South haven’t exactly been tolerant throughout history, but Kate Chopin showed them what feminism was all about. Most of Chopin’s canon is made up of short stories, being one of the few writers from the Louisiana Creole heritage. She did write two novels, though, including the famous feminist milestone The Awakening. Set in the South, The Awakening explores then-unorthodox ideas of what it meant to be a woman (i.e. femininity and motherhood). A stepping stone between the likes of William Wordsworth and Ernest Hemingway, Chopin embraced and propelled modernism—much to the dismay of Southern readers and critics.

7. Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888)

When women did write in the 19th century, they were expected to produce domesticated stories about romance and nature. So, when Louisa May Alcott published her vengeful sensation fiction, she had to use the penname A. M. Barnard. Later, her more family-friendly, transcendental novels bore her real name. Among them is the notably famous Little Women. Little Women has had numerous adaptations, musicals, rewrites, sequels, movies, operas, and radio shows. It remains continually referenced and parodied across all forms of media. Little Women centers on bold tomboy Jo, who rejects social expectations in favor of writing. You can probably guess that Jo is self-referential—Alcott based the story on her own childhood with her three sisters.

6. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825–1911)

If women were in the minority of writers back in the 1800s, then even fewer of them were black women. Not to say they didn’t write, but that they were often rejected for publication or simply forgotten by history. Of all the talented black female authors of the time who fought against double-glazed social barriers, we’re picking Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, the first African-American woman to get published. At just 20 years old, Harper was among the few black women to publish her own poetry collection. By her 60s, she was the first to print her own novel, too, called Iola Leroy. The social fiction conveyed all her strongest personal values: equality (of the sexes and races), abolition, education, responsibility, and temperance. Alongside this, she juggled teaching and public speaking.

5. Mary Ann Evans (1819–1880)

Mary Ann Evans is one of the few female writers who’s still better known by her penname, George Elliot. This pseudonym gave her more room to move beyond “female” themes of courting and pretty fields and into political topics. Of her seven novels, Middlemarch is heralded as the greatest. As a self-professed intellectual, Evans explored philosophical ideas of realism, agonism, and humanism. Even legendary modernist writer Virginia Woolf praised how smart Evans’s work was.

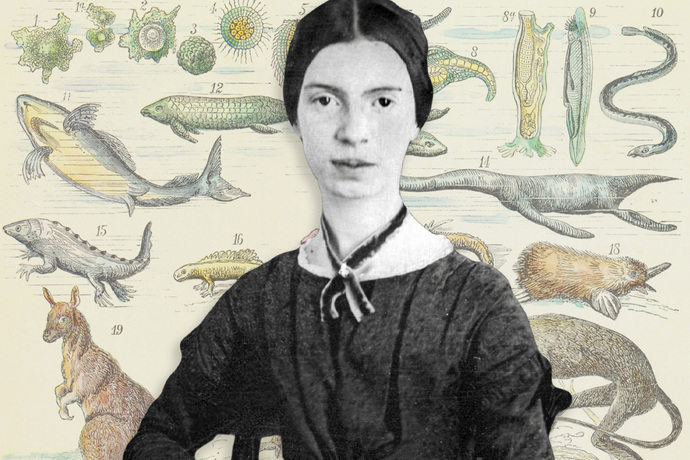

4. Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)

Emily Dickinson was the Vincent van Gogh of 19th century poetry—a little-known eccentric who became famous posthumously. Despite her family being a big part of their community in Massachusetts, Emily herself was a huge loner and recluse. And how did she spend all that time indoors? Writing 1,800 poems! Only ten of which she saw published, and even then heavily edited. Poetry has a lot more leeway in our current day. You can use all the enjambment you want, with no need to rhyme or even use capital letters. But back in the 1800s? Dickinson’s use of short lines, uneven rhyme schemes, and a lack of titles was considered flat-out weird. Dickinson’s isolation is now attributed to manic depression or schizotypal personality disorder. It was only after her death that Dickinson’s sister was able to read and publish her other works.

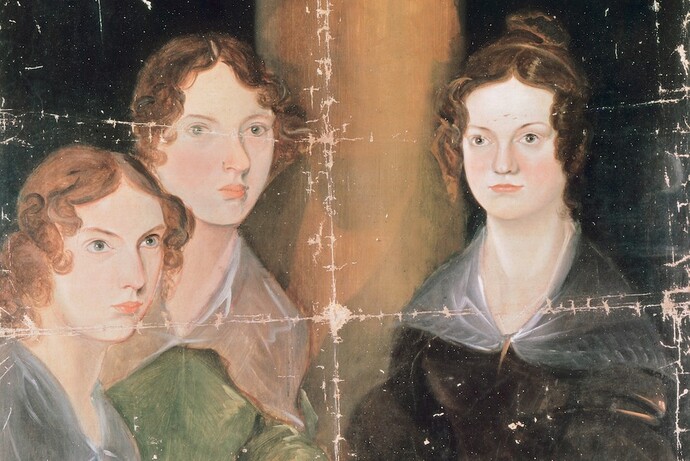

3. The Brontë Sisters (1816–1855)

Cheeky of us to put three authors in one entry, but we couldn’t have half the list dedicated to one family! And what a talented family. Eldest sister Emily Brontë was the oddball of the three, a shy rebel who published the abusive Gothic classic Wuthering Heights. That very same year, Charlotte Brontë published another British classic in Jane Eyre. Then, in 1848, Anne Brontë published The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Although it harbored the most shocking content of all the siblings’ daring novels, it was forgotten pretty quickly. Even to this day, Anne Brontë’s work remains less prominent than Emily and Charlotte’s work, probably because Charlotte suppressed its reprint after Anne’s death. (Her motive for this is still debated.)

2. Mary Shelley (1797–1851)

The Gothic genre was born in the 18th century, specifically from The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpol. That literary movement rippled into the 1800s, when Romantic writers picked it up and revived it. Of those Romantic writers, Mary Shelley is undoubtedly the most iconic for giving us the most famous Halloween character of all: Frankenstein (or, more accurately, Frankenstein’s monster). It’s well known that Mary Shelley conceived her idea for Frankenstein in The Modern Prometheus during one summer visit to Lord Byron, where the moody weather left the party with nothing to do except tell ghost stories. Imagine what we’d have missed if it’d been sunny!

1. Jane Austen (1775–1817)

Here she is! Jane Austen. A writer so famous, she basically has her own entire genre: sentimental period dramas about the British gentry. Everything from A Room With a View to Bridgerton to Bridget Jones’s Diary can be traced back to the famed English writer. Jane Austen’s six major novels use ironic social commentary to spotlight the restrictions women had to face at the dawn of the 19th century. Of them, only Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma were published during her lifetime—and even then, they were published anonymously, so she never saw her own fame. Read next: The Greatest Classic Books of American Literature, Ranked